What price will the UK pay for our lack of investment in higher technical skills?

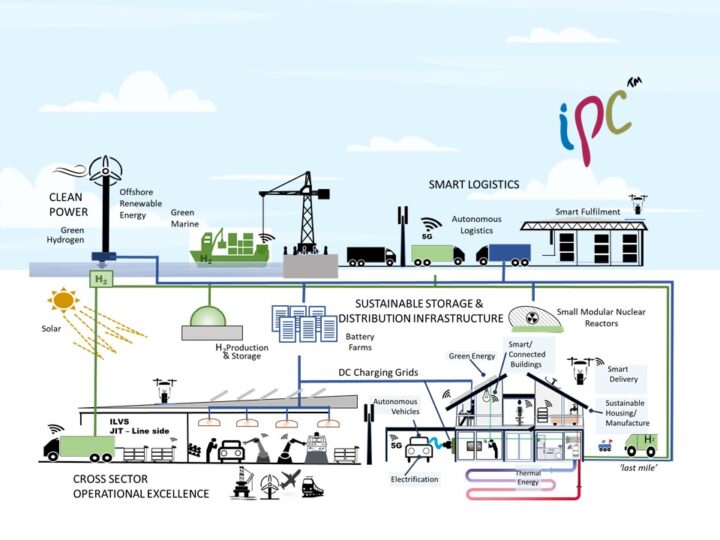

An ageing workforce, and the uncertainty of Brexit and the Covid pandemic, is causing a perfect storm in the UK employment market and exposing the scarcity of higher level technical skills needed to develop and deploy the new technologies required to deliver the commitment to net-zero emissions. The impact on sectors such as Construction and Hospitality of more than one million migrant workers leaving the UK during the pandemic has been widely reported, but for some time the UK has also relied on skilled migrant labour to plug a gap in its technical skill base across different sectors. Many of our clients have referred to their past dependency on sourcing higher level technicians from Eastern Europe, but the backdrop of Brexit and the pandemic has prompted many to leave the UK, at a time when demand for those skills is accelerating. These skills take time to develop, and our recent over-reliance on other countries supplying these skills now threatens our ability to realise the growth opportunity provided by new technologies. The Department for Education has just announced a new Growth Fund to enable education providers to expand their higher technical education offer. This represents a very positive development, but there is still much more to do if the UK is to establish the supply of higher technical skills it needs to develop and maintain an advanced digital estate across emerging technologies, and provide a pathway to net zero.

So why is there a shortage of higher-level technical skills?

Collectively we have taken our eye off the ball on developing a pipeline of advanced vocational technical skills. Within 10 years of leaving school around one-third of leavers will have reached degree level and another quarter will have attained A-levels or other level 3 qualifications, but staggeringly only 4% will have progressed to level 4 (HNC) or level 5 (HND/Foundation degree). The proliferation of the HE sector will have motivated many to pursue a degree programme, when some may have been better served pursuing a technical vocational qualification. The apprenticeship levy was meant to encourage employers to support more vocational learning, but it appears to be missing the target. Many levy-paying employers report that there is limited flexibility on how they can spend their levy, resulting in them not being able to fund their current and future upskilling and reskilling needs, and also not spending all their levy. The most popular higher apprenticeships in Engineering are now Level 6 Degree apprenticeships, and only 2% of new apprentice starts are at Level 5. Meanwhile new technologies, digitalisation, and strategic infrastructure projects are all driving demand for higher-level technical skills, at a time when many skilled technicians are reaching the end of their careers and skills are scarce. These skills often take at least 5-6 years to develop, and employers have had limited ability to forecast and fund the training required to meet future demand.

What’s the response?

UK Government has recognised the importance, and the gap, in technical skills at level 4 and 5, and in 2019 launched twelve new Institutes of Technology (IoTs) to help address the issue, and plan to licence a further eight later this year. They have high aspirations for IoTs, requiring collaboration between Higher and Further education to align educational provision to future regional business need, that is directly informed by the latest research and emerging technologies. Capital funding is provided to the IoT partners, secured against a promise to deliver a step change in the number of Level 4/5 technical vocational qualifications. The Government has also recognised the importance of reskilling and upskilling the existing workforce, and recently announced funding to support the development of short and modular courses in higher technical skills. Leveraging the advanced manufacturing research capability available in the High Value Manufacturing Catapult centres to support curriculum development is also recognised, and the IoTs provide the opportunity to serve as regional Centres of Excellence to tailor and deliver that curriculum to meet the future needs of the local economy.

How should the response develop to meet future needs?

We have recently completed a strategic review of one of the first wave IoTs, and our findings point to some important implications for the future supply of UK technical skills.

- If Universities are serious about contributing to their local economies and inclusive growth they must engage in the development of a local business and skills ecosystem by leveraging their research capability in emerging technologies and providing broader access to their expertise. This will include using that research in collaboration with other local education providers to enrich the vocational curriculum for technical skills from Level 3 through to Level 6. Best practice illustrates that in mature ecosystems learners transfer this knowledge back into local SMEs, and enable the early adoption of new technologies and emerging innovation that drives growth. The Department for Education view the IoT as a regional franchise, and the IoT partners need to share an ambition to make a meaningful contribution to the broader regional economy, which may extend beyond the traditional space occupied by each partner. Last year the Independent Commission on the College of the Future called for an impactful post-16 education and skills system that addresses unproductive competition between institutions. Collaboration between in-region partners will be key if the IoT is to achieve the right balance that enables it to become a true Centre of Excellence for technical skills that also provides inclusive access to learners and employers through the geographic reach of its partners. Regional stakeholders will benefit from the ‘whole being greater than the sum of the parts’.

- Education providers must invest in effectively engaging SMEs at scale, with an accessible, affordable, and flexible offer that provides business value. SMEs account for 3 out of every 5 private sector jobs in the UK and contribute to approximately half of private sector turnover; they are the backbone of the UK economy. They tend to have shorter planning time horizons, but they are agile and alert to growth opportunities, and need to be fully engaged in vocational learning and skills development. Providers often prefer working with larger organisations which can help supply a higher volume of learners, but SMEs are key to the prosperity of local economies, providing the drivers for growth and good jobs in engineering, technology, and advanced manufacturing.

- Proactive funding for the new curriculum to meet future requirements is critical. The High Value Manufacturing Catapult should continue to play a leading role in developing this curriculum, in collaboration with IoTs, to support emerging technologies and industrial digitalisation. One-off capital funding for colleges to buy new equipment or improve infrastructure is not in itself the solution. History shows that it often stands underutilised, quickly becomes obsolete, and will typically provide less value than the latest equipment available in research facilities sponsored by universities or industry. Apprenticeship Levy funding needs to be more flexible to match business need. There is still only a limited apprenticeship offer at Level 4 and Level 5, and the levy can’t currently be used to fund part-time HNC, HND or Foundation Degrees outside apprenticeships, or to fund modular CPD programmes to enable upskilling/reskilling.

- Removing barriers to accessing higher level technical skills needs to be a priority, to enable more inclusive growth. Technical and digital skills provide access to better jobs – jobs that require Level 3-5 educational attainment and advanced digital skills will pay an average premium of around £6,000 over those not needing the advanced digital skills. Female and BAME participation in higher-level apprenticeships in engineering and manufacturing technology continues to be low, representing a missed opportunity to both attract diverse talent and capability and achieve a more equitable distribution of the benefits of good well-paid jobs and careers.

At IPC Sean McIlveen and Bob Blenkinsop provide advice to public and private sector clients on organisational and working practices, workforce development and productivity.

Recent Comments