Who’s going to ensure we have the skills to deliver the Industrial Strategy?

Dilemma

It is estimated that there is an opportunity for UK business to exploit a £5bn GDP growth opportunity through Power Electronics, Motors, and Drives (PEMD) products in the next 5 years (and £80bn by 2050). However, it appears unlikely that we will have sufficient electrical engineers to resource the supply chain to develop and deliver these new products.

This real dilemma highlights one of the challenges associated with delivering the UK Industrial Strategy. How do we access the skills and workforce we need to deliver future growth opportunities?

Posing this question, prompts other supplementary questions.

- How do we anticipate future capability requirements?

- How do we do this in advance of a clear demand signal being available from industry?

- How do we align education and training provision to supply that capability?

- How do we do it in a timely manner, given the long time it takes to develop skills in technology and technical subjects?

As all the challenges featured in the Industrial Strategy require the development and application of technology, which will depend on similar STEM skills, these questions assume more importance.

UK Industrial Strategy Grand Challenges

| Artificial Intelligence and Data | We will put the UK at the forefront of the AI and data revolution |

| Ageing Society | We will harness the power of innovation to help meet the needs of an ageing society |

| Clean Growth | We will maximise the advantages of UK industry from the global shift to clean growth and low carbon technologies |

| The Future of Mobility | We will become a world leader in shaping the future of mobility |

Some businesses are already acting to address their future workforce requirements, and the Dyson Institute and the Siemens Digital Academy are both good examples. Whilst there is much to be admired, and learned, from these programmes, they will not service the wider talent needs of industry. Many businesses, including SMEs, will not have the scale, capability, confidence, or employment brand, to replicate these programmes.

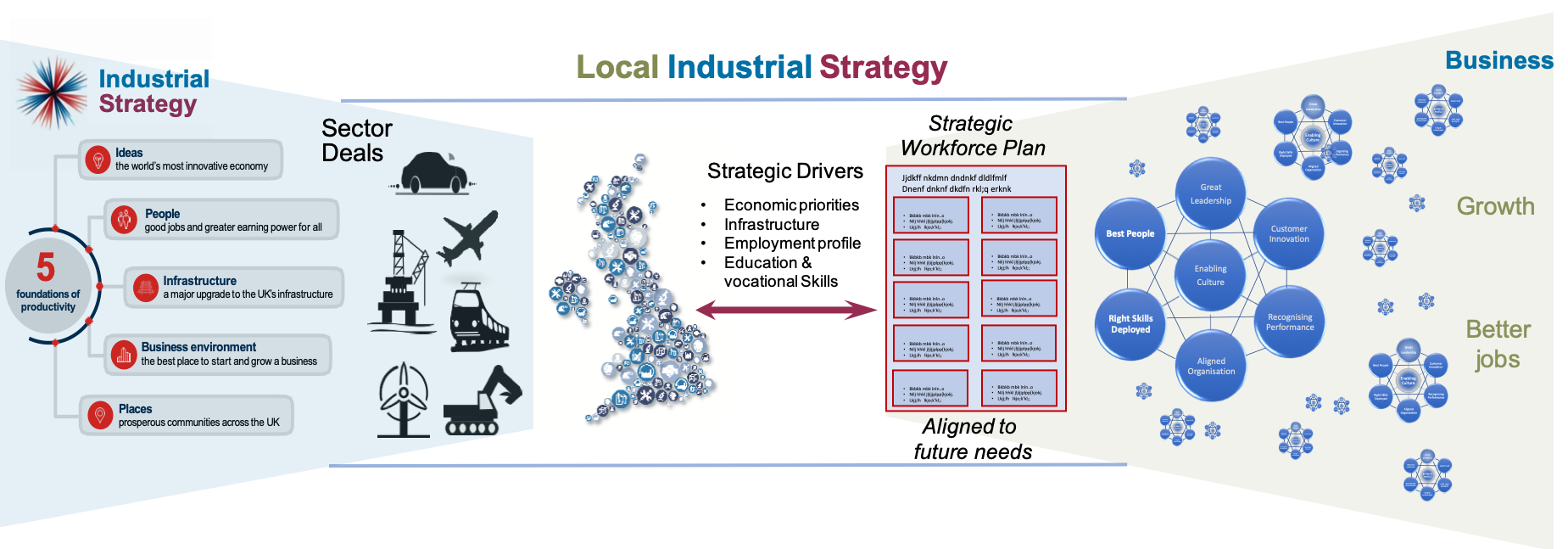

We believe the UK has the ability to deliver these skills, but for this to be done effectively, there does need to be a more long-term, deliberate, and integrated approach to workforce planning, at both a local and national level. In this post, we consider some elements that should form part of that approach.

Provide a proactive strategic demand signal into education, and incentivise providers to deliver against it

Several sector deals, describing strategic challenges and opportunities, have been developed as part of the industrial Strategy, and some include a People or Skills element. This should be a starting point, and it will be important to look across them, and identify key capabilities that are relevant across sectors. The PEMD opportunity is a good example – the same skills will be required in aerospace, automotive, rail, marine, and power generation, and crucially, they will be required to develop a shared supply-chain that can support all of these sectors. This doesn’t just apply to higher-level engineering skills. Core foundation skills, including basic digital and communication skills, will be needed across all sectors. Delivering a larger pool of these core and strategically important skills will provide better career prospects, and a more resilient and flexible labour pool over time.

Once these strategically important skills are identified, education providers will need to be incentivised to increase capacity and participation on relevant programmes. In the same way that finance is made available to support strategic research and infrastructure projects, funding should be targeted to support strategically important educational outcomes.

High quality education and training outcomes, developed and delivered by best-practice providers

Effectively translating the strategic demand signal into world-leading capability and skills will require outstanding STEM curricula development and delivery. There should be focus on leveraging best-practice providers, and using them to help develop a collaborative national network of centres of excellence for technical and STEM education and training. The existing High Value Manufacturing Catapult already has proven capability to translate advanced manufacturing research into an enhanced technical curriculum. The AMRC at Rotherham and the MTC at Ansty are already leveraging their research capability to provide an enhanced curriculum to different audiences, from skilled technicians through to degree and post-graduate students. The Warwick Manufacturing Group also do this through their Degree Apprenticeship Centre, and partner with the Dyson Institute on their electrical engineering degree apprenticeship programme.

A collaborative network across this group, and those engineering employers already delivering high-quality technical training, could provide good sector and geographic reach. The integration of the new Institutes of Technology, recently announced by Government to improve the delivery of Level 4-5 STEM programmes, will further enhance this delivery capability. This extended network will be particularly important in building capacity and capability that is accessible to SMEs.

Place based workforce planning

Ultimately skills need to be available in the places where employers need them, and there should be some form of local accountability for this. As almost half of us will only ever work in the place where we’re born, this will include a focus on social inclusion and ensuring schools and colleges are equipping local people with the core foundation skills and qualifications employers need, as well as attainment levels which enable access to vocational and academic pathways. There are also needs to be a local “offer” that attracts and retains skilled workers, encompassing housing, transport, and other facilities.

A local workforce plan therefore needs to be grounded within an integrated Local Industrial Strategy. The plan also needs to anticipate and manage future risks to employment. The flip-side to digitalisation and new technologies is that some places will be particularly vulnerable to structural change as some sectors, products or technologies decline. Planning for this will include developing transferable skills among those currently employed, and the new National Retraining Scheme should support this.

Returning to our dilemma regarding resourcing growth in Power Electronics, there will need to be reactive measures in the near-term that help secure the immediate opportunities. It should though provide a wake-up call regarding the need for more focus on workforce planning, at both a national and local level. If we are to realise the goals of the Industrial Strategy and provide sustainable local economic value through more and better jobs, we will need to ensure we have the workforce that are skilled to meet the challenge.