Inclusion – imperative for industrial growth

In this post we suggest that without a more inclusive economic, social, and education system, and employment practices, the UK is unlikely to achieve its Industrial Strategy. We highlight three particular challenges that will need to be addressed through an integrated approach to workforce planning:

- Greater social mobility and inclusion will be needed to ensure the future workforce has the foundation skills and qualifications required

- A more inclusive approach to employment will be needed to engage a larger pool of potential employees to meet future demand

- A more diverse pipeline of STEM talent will be needed to provide the innovation and industrialisation capability required to exploit high value growth opportunities offered by new technologies

Background

The ambition of the Industrial Strategy includes creating “good jobs and earning power for all” and this is reflected in the emerging Local Industrial Strategies and Economic Plans across the UK. In the North East, for instance, its about the creation of 100,000 new jobs in the decade up to 2024, with 70% being “better” jobs, defined as managerial, professional, and technical roles. Despite some short term softening in the employment market, the long-term outlook and industrial strategy assumes growth, which brings with it a risk that the supply of skills may be inadequate unless these challenges are addressed through a more integrated and inclusive approach.

Greater social mobility and inclusion will be needed to ensure the future workforce has the foundation skills and qualifications required

There aren’t currently enough people qualified to fill the number of “better” jobs being targeted, and there are significant social issues limiting opportunity to acquire the required qualifications. Only 40% of the current workforce in the North-East are in roles defined as “better” jobs, and only around half have attained the levels of qualification they typically require. Most disadvantaged young people are struggling to get anywhere near to these roles, and more than half of Free School Meal eligible pupils will not have Level 2 (GCSE equivalent) qualifications in Maths and English by the age of 19.

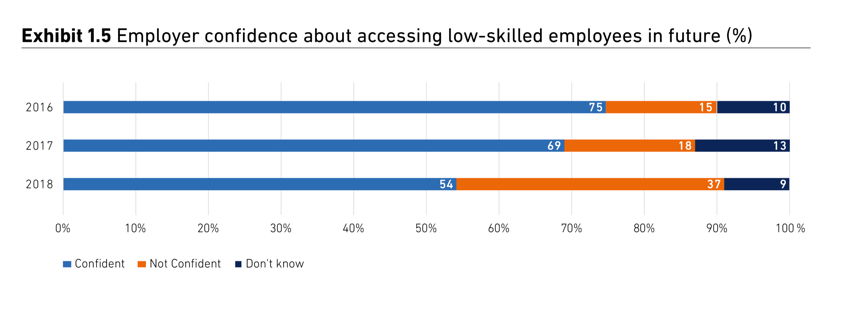

Employers often tell us about the challenges they face attracting good quality candidates into entry-level or lower-skilled roles, and this declining confidence is illustrated in the 2018 CBI/Pearson Education and Skills Survey (Figure I), which suggests only around half of employers are confident about accessing low-skilled employees in the future.

Figure I

Source: CBI/Pearson – Education and Skills Survey – 2018

A complex range of social factors impact the educational attainment of disadvantaged groups. They are less likely to be taught Maths and Physics by teachers qualified in those subjects, and they are 4 times more likely to be excluded from school. Certain groups will be disproportionately impacted – BAME adults are twice as likely to be living in poverty, and their children are more likely to be caught in this cycle of disadvantage.

A more inclusive approach to employment will be needed to engage a larger pool of potential employees to meet future demand

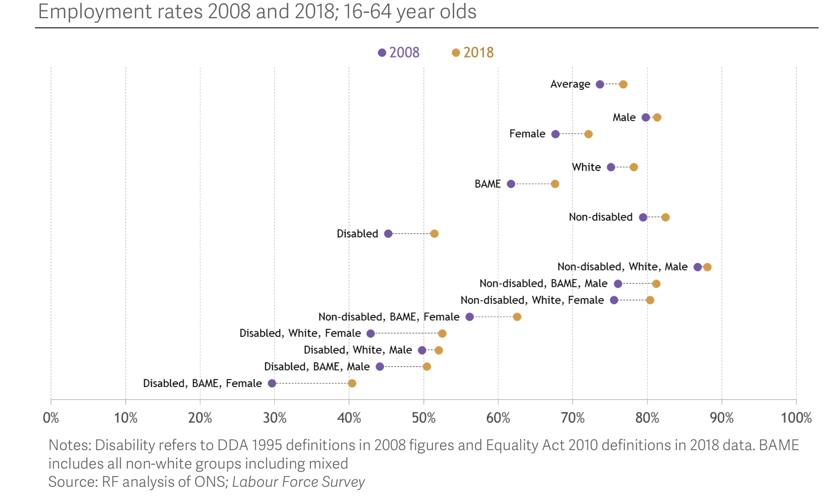

Reduced migration, particularly from the EU, will present new challenges for employers. Figure II illustrates that the tighter employment market in recent years has provided more access to employment for under-represented groups, but it is still far from a level playing field, and women, BAME, and those with a disability, are still significantly less represented in the workplace.

Figure II

Source: Resolution Foundation – Structural Inequality in the UK -October 2019

Employment practices and workplace culture will need to be inclusive, recognising the needs of a more diverse workforce that will include more females, more workers age 50+, and more people with a disability.

A more diverse pipeline of STEM talent will be needed to provide the innovation and industrialisation capability required to exploit high value growth opportunities offered by new technologies

The industrial strategy has a strong dependency on leveraging technology to develop innovative scalable solutions to complex future challenges. STEM capability is key, and currently there is a gap in the supply of skills needed in certain areas. The ability, for instance, to exploit the emerging growth opportunities in Power Electronics is currently constrained by the shortage of electrical engineering graduates available. The uneven education playing-field limits access for some, but the under-representation of females in STEM subjects continues to seriously constrain the supply of available talent. Currently around 1 in 3 STEM graduates are female, and the engineering workforce is less than 15% female. This challenge of attracting females to STEM subjects and careers is well documented, and is already the focus of several employer-backed initiatives. These will need to continue, and extend to SMEs, as it remains a key enabler of increasing the available pool of talent required to develop and industrialise new technologies in the UK.

Complex challenges – require an integrated place-based workforce plan

There is clearly a systemic inter-relationship between these challenges, none of which are new or easily resolved. However, progressively addressing them through a sustained plan will be needed if the UK, and its regions, are to achieve the ambition to create more and “better” jobs. A place-based approach to addressing social mobility is essential – around 45% of us will only ever work in the place where we are born. So those towns, cities, or regions, with ambitions to transform their economies and the employment prospects for those in disadvantaged areas by attracting investment and higher-skilled jobs, will need devolved powers, strong leadership, and an integrated road-map to address these challenges. Otherwise, the local population may simply be excluded from these opportunities, and businesses will struggle to attract the workforce and skills they need to succeed and grow.