Workforce Planning – time to step up to the plate

It’s clearly going to be a busy new year for business and political leaders, but results of a survey by the British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) released last week highlighted further challenges needing their attention. BCC reported that businesses are finding it as difficult to find the right staff now, as it has been at any time since their survey began in 1989. 81% of those recruiting in manufacturing, and 70% of those in services, reported difficulty in finding the right people.

Despite current economic uncertainty, data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS), suggests this challenge isn’t going to go away in the near-term.

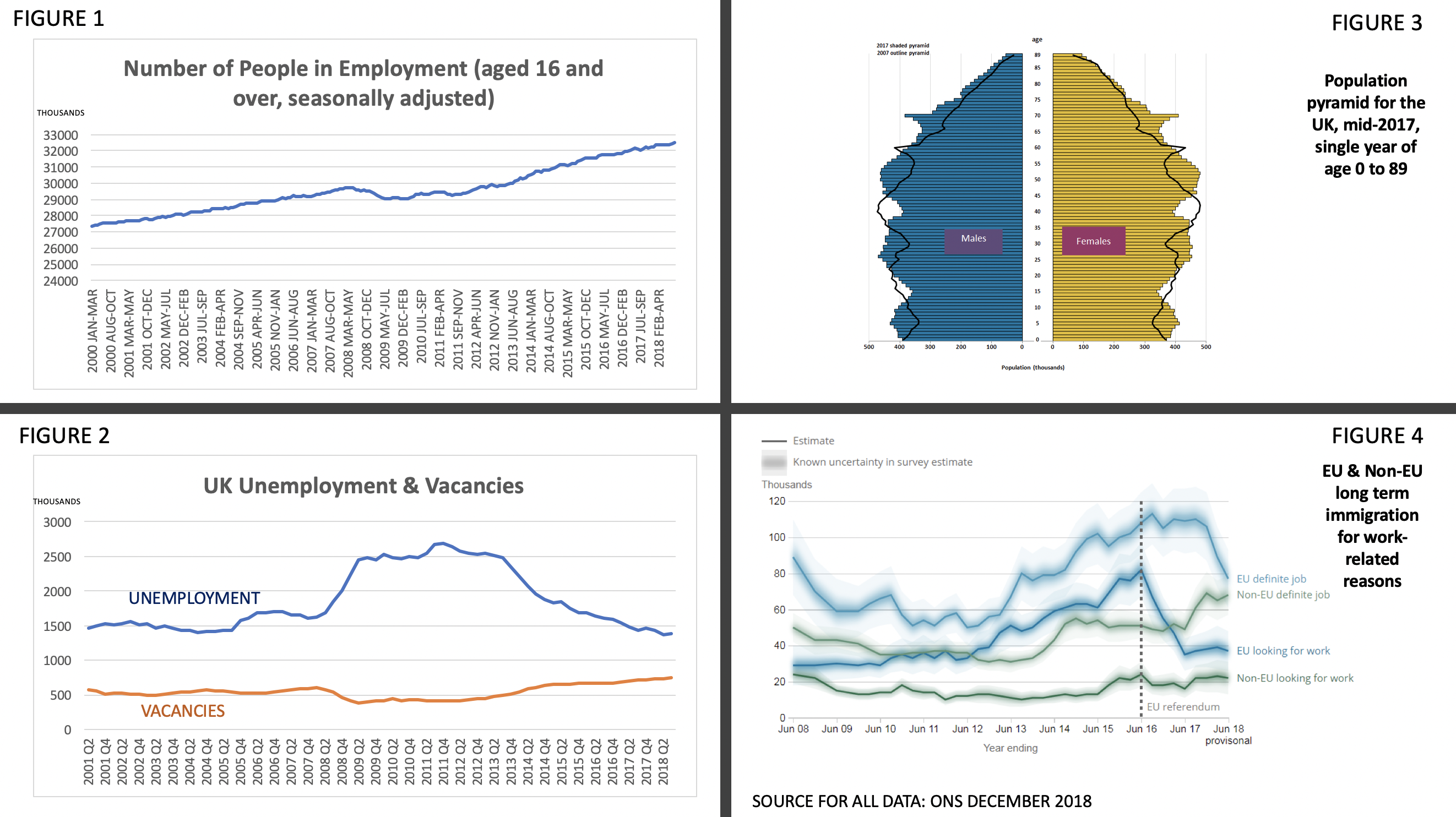

The demand for people to fill jobs continues to be high– the number of people in jobs in the UK has grown by 5 million since 2000, and the number of job vacancies is at its highest level since records began, up around 5% in the last 12 months.

The number of available people in the labour market is reducing– unemployment is at its lowest level for 50 years, migration from the EU has halved since the 2016 Brexit referendum, and the numbers of young people entering the labour market during the next 5 years will be significantly lower than the numbers leaving it.

And if it wasn’t hard enough already, the challenges associated with sourcing the right-people will be compounded by changes in the mix and levels of skills required, as more automation in the workplace eliminates many routine tasks.

Entry-level roles in many sectors will need to perform a broader range of tasks and will require basic digital skills, accompanied by higher levels of cognitive and interpersonal skills, as employees need to effectively interact with data, machines and each other, in a more distributed workplace. A World Economic Forum survey of business leaders suggests that more than half of us will need some level of re-skilling by 2022. Different sectors will face further challenges related to skills, driven by changes in the market, technology, or regulation.

Some of the implications for business leaders are clear. With limited availability in the external labour market they’re going to need to have a workforce plan which:

- anticipates their future requirements.

- develops and re-skills their existing employees.

- builds a robust pipeline of skills for the future.

- broadens access to opportunities through a more inclusive approach to employment.

However, improved planning at an individual business level won’t be sufficient to address all the issues caused by a scarce supply of qualified people. Those businesses with the resource, capability, and employment brand to attract candidates are likely to prevail in any competition for scarce skills, but the impact on the local employment market is likely to be disruptive, and particularly detrimental to small and medium sized businesses.

The importance of SMEs can’t be overlooked here. They provide 60% of private sector employment in the UK and contribute around half the national income, but often find it difficult to equip their workplaces with the automation, management practices, and skills required to improve productivity. Productivity and providing “good jobs and greater earning power for all” is central to the Government’s Industrial Strategy, but UK levels of productivity have continued to lag other G7 economies since the last recession. Enabling SMEs to access the supply of skills they need must be part of the response, and this will require regional and sector-level workforce plans to be integrated into local industrial strategies.

There is no easy or quick fix for this. Creating more “good jobs” and a current and future workforce with the skills to do them, requires a consistent, long-term strategy, and a lot of leadership, resolve, and hard work to execute it. It needs regional workforce plans informed by sector requirements and enabling cross-sector synergies, which are underpinned by aligned policy, and real partnership between business, education, and government. Businesses and sectors will need to better articulate their future requirements into an aligned education and training system, which will need to more effectively deliver the skills and attainment levels needed. The plans will need to be dynamic and managed, so that they can respond to new requirements resulting from changes driven by automation, technology, or market factors.

Clearly, all this won’t be achieved in 2019, but it could be the year that workforce planning emerges as a more integral part of local industrial strategies being deployed across the UK. Let’s hope so.